LATEST HOT NEWS IN THE ROOM

The 6th President Hon. Moses Wetangula

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

For two general elections, Moses Masika Wetangula has been one of four principals in the main opposition coalition, and is now a speaker of the national assembly, hoping and very well assured that he will ascend to state power. To Wetangula, being a speaker of the national assembly is a good political arithmetics, since he is among the first equals, and he hopes that if not now, then one day his turn to become a first shall come. In this three-part read, a blogger editor and in-Chief executive Paul masibo goes back to his two hour conversation with Wetangula, in which he examines the Bungoma Senator’s tenacity and staying power, and what his presidency - if and when he becomes a first - will look like and mean for Kenya.

Part 1: From Meek Catholic Boy To Gutsy Rookie Advocate

When Senior Private Hezekiah Ochuka and his batch of Kenya Airforce accomplices - Pancras Oteyo Okumu, Joseph Ogidi Obuon, Charles Owira, Walter Odira Ojode and Bramwel Injeni Njereman set out to overthrow the four year old government of President Daniel arap Moi on 1 August 1982, they weren’t aware that the coup d'état would abort, after which they would flee to neighboring Tanzania where they would get betrayed and handed over to Kenya to face court martial, in which instance no advocate would agree to defend them.

As the mutiny unraveled and got foiled, 26 year old Moses Masika Wetangula was similarly unaware of just how much the events of the day would shape his personal and professional lives. As a curfew was enforced to deal with remnants and aftershocks of the insurgency, Wetangula and his classmates at the Kenya School of Law (KSL) on Valley Road got locked up for two weeks at Groven Hotel, which was located opposite present-day CITAM Valley Road, and whose exact location is part of the Department of Defense headquarters today.

Save for a last minute expulsion from Friends School Kamusinga just two months shy of his sitting for his A Level finals on what he terms flimsy grounds - he was accused of inciting students against the head teacher,Wetangula had had an otherwise pious-looking Catholic upbringing, such that mentioning his name and the word coup in the same sentence would seem like a rich stretch of one’s imagination, whatever context the word coup would be used in.

Growing up in a cordially co-existing polygamous family of 30, it was imperative that from an early age, Wetangula had to learn to get ahead of the curve one way or another. 15 children were born to his mother, comprising four sets of twins and seven singles. Wetangula, who was the fourth born, was one of the singles alongside his baby brother Tim, the MP for Westlands.

Coming after an elder sister who passed on young, followed by a twin brother and sister, followed by yet another sister who succumbed young, Wetangula was the de facto firstborn in the homestead, considering the twin brother was being groomed to become a priest and was enrolled in a seminary, while the twin sister was sent to boarding school pretty early.

‘‘I started school in 1964 aged 8 years old when I joined Nalondo Primary School,’’ Wetangula says when we speak at the wide gazebo at his humongous Karen home. From where we sit, at the back of the single storey residence, one encounters a well manicured lawn almost the size of a soccer pitch, littered with palm trees. On one end of the compound is a long driveway leading to the main entrance of the house, where one finds a stretching garage for three and an elongated eco-friendly carport which can hold up to about a dozen vehicles. And when one follows the driveway back-out, it leads into a second half of the property, a banana plantation. The other flank of the home has above-average-sized guestwings, servants and boys’ quarters.

A swimming pool is cooling off next to us. We’re stationed not too far from the kitchen.

From Wetangula’s home in Mukhweya village in Bungoma, Nalondo was about 5 kilometres away, not the closest school. A kilometer away was Namilama DEB Primary School, but because it wasn’t Catholic, Wetangula had to brave the distance to the Catholic Nalondo.

‘‘Due to the huge distances between homes, and because of roaming wild animals - I could hear hyenas laugh on my way to school,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘we had to go to school as a group with other children from the neighbourhood.’’

But what would happen if one couldn’t meet the rest of the kids on time?

‘‘My mother would hear none of it,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘you’d have to walk to school alone.’’

It is in the spirit of moving as a pack that Wetangula’s mother ordered that as much as lower primary kids were released from school at noon, Wetangula had to stay in school and come home after 4pm when the rest of the school left for home. This way, he would get more time to study, before getting lost in picking coffee or weeding maize, depending on the season.

And yet, walking 5 kilometers to Nalondo must’ve been preparing Wetangula for the future.

‘‘I used to walk for 30 kilometers daily,’’ Wetangula says of his early days in high school, ‘‘on the road from Mukhweya through Namilama, Malinda, Chwele, Chebukaka to Teremi,’’

Ideally, Wetangula would have found a place at Friends School Kamusinga for his form one, but unfortunately, much as he had excelled in his Certificate of Primary Education, his head teacher at Nalondo failed to submit the candidates’ school selections on time, leaving them in post-exam limbo. This is how Wetangula did his first year at Busakala Secondary School, before an uncle adopted him and took him to the better-performing Teremi High School, where Wetangula agreed to repeat Form One as a prerequisite for admission. Unfortunately, his uncle could only afford the tuition fees of Ksh. 450, meaning he had to be a day scholar.

Teremi was 15 kilometers away from Wetangula’s home.

‘‘There was a bus company called Mawingo,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and there was a driver called Bakari who drove one of the buses on the Bungoma-Kitale route. He used to see me walking along the road every single weekday with my school bag, until one day he stopped the bus.’’

Bakari: Young man, where do you go every morning? I see you carrying a school bag.

Wetangula: I go to Teremi.

Bakari: You go that far on foot?

Wetangula: Yes.

Bakari: From now on I will be giving you a lift to school.

That particular Mawingo bus used to pass by Wetangula’s Mukhweya home at 6.30am, and by 7am Wetangula would be at Teremi. Bakari eventually took Wetangula to meet the owner of Mawingo, an Arab man called Abdul Karim, to whom Bakari presented Wetangula’s case. Abdul gave Wetangula a bus pass which he used everyday for 3 years. Considering the last bus from Kitale to Bungoma passed Teremi at 4pm, Wetangula skipped games to catch the bus.

‘‘When I got to Form Four I told my uncle I needed to be in boarding school,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He agreed to pay the boarding fees of Ksh. 150. Unfortunately, once again the head teacher didn’t forward our school choices on time, leaving us stranded with excellent results.’’

Luckily for Wetangula, his uncle reached out to Kamusinga and he was offered A Level placement.

At Kamusinga, Wetangula was classmates with former Cabinet Secretary for Health Cleopa Mailu and former Webuye MP Saulo Busolo. It was here that he got the opportunity to play sports, forming part of the Kamusinga soccer team which won the national championship. It was also here that Wetangula got fascinated by the likes of James Orengo and Oki Ooko Ombaka, who had both been student leaders and turned out to be firebrand lawyers.

He, too, had to become a lawyer.

It was in possibly getting ahead of himself as a wannabe lawyer that Wetangula took to speaking at the school Kamukunji with a little more gusto than had been the practice, a slippery slope which resulted in his expulsion alongside his two Form Six classmates, Peter Masengeli and Martin Rodgers Mutende. They had to be given police escort as they sat for their A Levels. This was the first time Wetangula was going against established order.

‘‘I was so confident I would become a lawyer, so much so that when I was picking my three degree courses,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘I put law as my first, second and third choice.’’

Wetangula survived the expulsion, making the cut for the Faculty of Law at the University of Nairobi. Here, other than playing soccer with the likes of JJ Masiga, Wetangula’s life was largely lived on the straight and narrow alongside members of the infamous class of 1981 which included National Assembly Speaker Justin Muturi - who was Wetangula’s first year roommate, Justice Mohammed Ibrahim of the Supreme Court, Justices Fatuma Sichale and Jessie Lessit of the Court of Appeal, Justices Boaz Olago, Aggrey Muchelule, Fred Ochieng, Joseph Karanja, Roselyn Wendo, Martin Muya and Kaburu Bauni of the High Court, former Ministry of Lands PS Dorothy Angote, Federation of Kenya Employers executive director Jacqueline Mugo and former High Court registrars Jacob ole Kipury and Charles Njai.

After graduating in October 1981, Wetangula joined the Kenya School of Law (KSL), where the coup found him. Aside from the coup, the year at the KSL flew past quickly and uneventfully.

The group exited the KSL in October 1982.

What followed was Wetangula’s chaotic albeit brief judicial stint. First sent to Nakuru as a District Magistrate 2 - where he could hear between four to five matters a day - Wetangula was quickly dispatched to Kithimani in Machakos, where ‘‘there was no work. You could stay for a week to handle one or two cases, with the courtroom located behind a shop.’’ After complaining to the judicial honchos in Nairobi, Wetangula was transferred to Kisii, where he found an overload of magistrates, from where he was sent to Rongo. It was February 1983.

‘‘My father had decided, and decreed, that I take responsibility for educating all my siblings,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘I decided that to be able to shoulder the huge responsibility bestowed upon me, I had to look for better ways of making ends meet. I resigned as a magistrate.’’

Wetangula arrived in Nairobi with nothing but Ksh. 2,400, his last salary as a magistrate.

Luckily, David Malakwin, Wetangula’s classmate from the University of Nairobi, had gotten employed by the Kenya Posts and Telecommunications Corporation (KPTC), and was given a three bedroom staff house at the junction of Ole Odume Road and Ngong’ Road. Malakwin invited Wetangula over, alongside their other classmate and future registrar of the High Court, David ole Kipury, who was working as a magistrate in Nairobi. Malakwin, Wetangula and ole Kipury each took a bedroom, with Wetangula and ole Kipury contributing 500 bob each to go towards water and electricity. Food was bought jointly by the trio.

‘‘We lived very well together,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘until such a time when we each decided to move out and start our own families.’’

For work, Wetangula found a similar quid pro quo arrangement.

Murtaza Jaffer - who became one of the founders of Kituo cha Sheria and a judge at the industrial court - had an office on Luthuli Avenue, next to Ramogi Studio. Like Malakwin, Jaffer invited Wetangula and Wetangula’s classmate and future Supreme Court Justice Mohamed Ibrahim to share his office, only that they wouldn’t pay for their tenancy in cash.

‘‘Jaffer had a lot of trade union work,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘and so the arrangement was that we do his work in court for no payment, and share his offices for no payment as well.’’

It was around this time that Wetangula received the Ochuka brief from a senior politician, who he declines to name for now, for potentially obvious reasons.

‘‘I happen to know that rounds were made across the chambers of notable advocates, those considered established enough to not be wary of the Moi state,’’ Wetangula says of the hunt for counsel to represent Ochuka and others. ‘‘All of them gave the brief a wide berth.’’

At the time, Kenya was a de jure one party state, and following the attempted coup, an injured and emboldened President Moi had issued an infamous warning to the plotters and their real or imagined sympathizers, ‘‘nitawawinda kama panya mpaka kwa mashimo.’’ A flurry of house arrests and detentions without trial were to follow as Moi firmed up his grip on state power.

‘‘I will not say who my instructing client was, but a very senior politician sent for me, and asked me if I could take up the cases,” Wetangula says. “Considering the trials could result in a death sentence, the military was also obligated under the law to ensure all the accused had legal representation. This too was a factor in my accepting the brief.’’

Everyone thought Wetangula was insane.

‘‘My father was very frightened,’’ Wetangula says. ‘‘He jumped on a bus, came to Nairobi and came to my office. His instruction was, ‘‘Leave these cases alone. You are going to bring problems to yourself and to the family.’’ I told him Daddy I won’t leave the cases because I know I am doing the right thing and history will absolve me. I asked him to go back home to the village and not talk about the cases to anyone because he knew nothing about the brief.’’

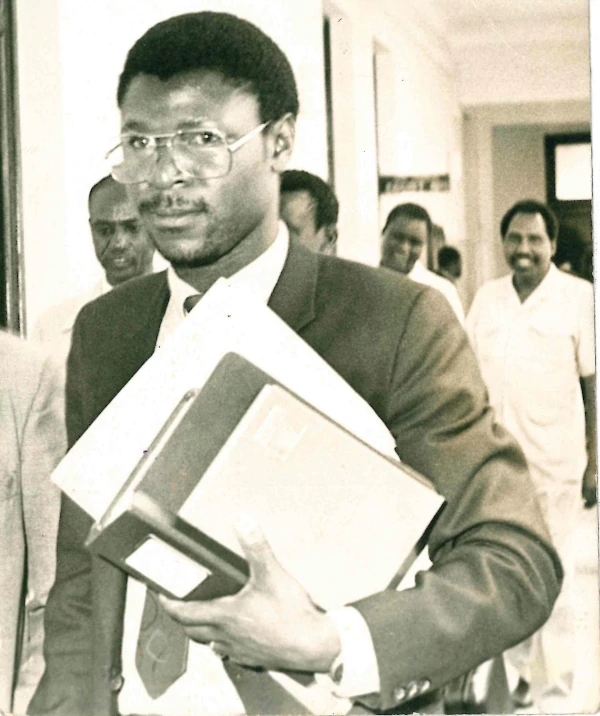

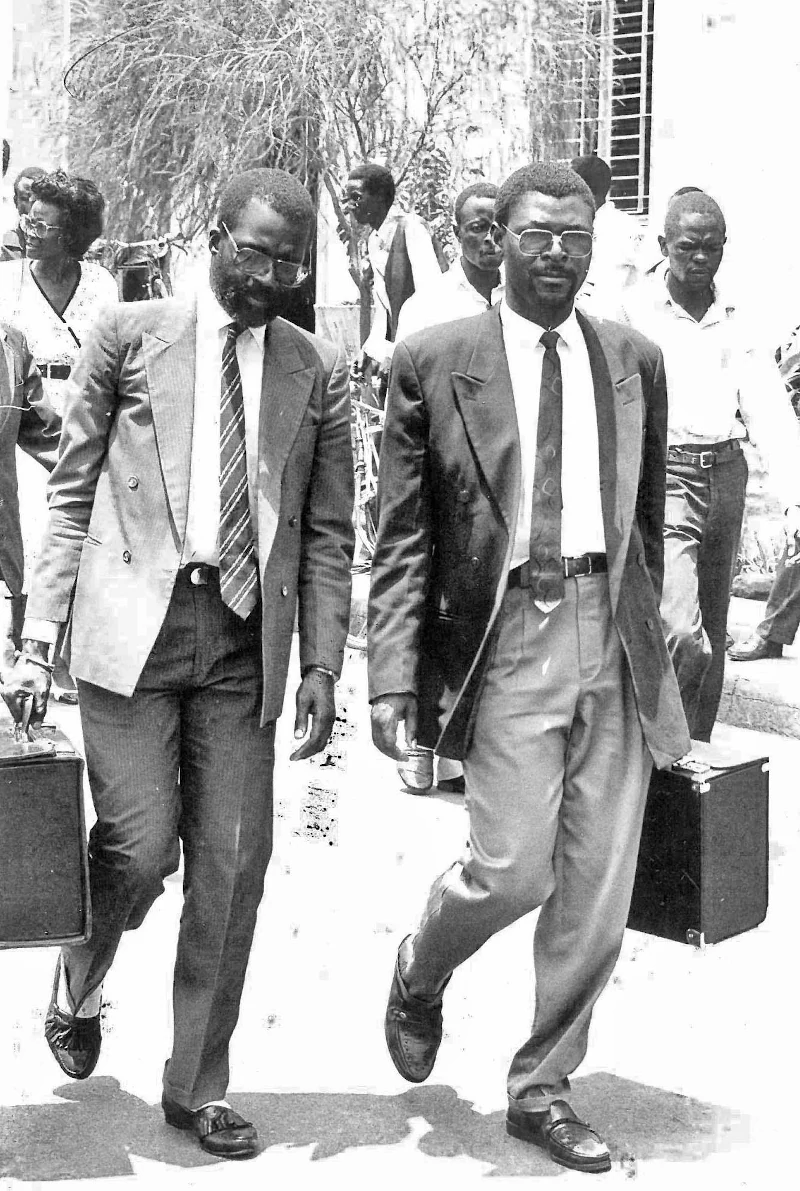

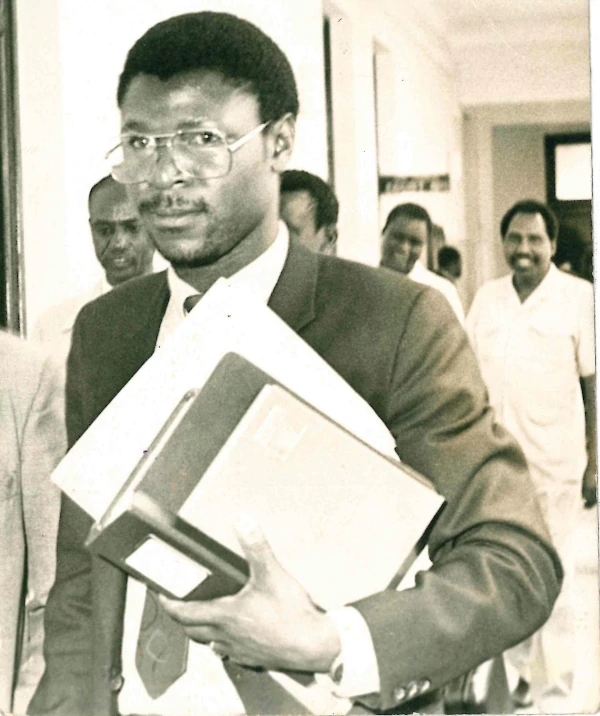

As the cases got underway at court martial at Langata Army Barracks, Wetangula’s notoriety within the legal fraternity went through the roof.

Who was this crazy enough kid representing mutineers at such a dicey time?

‘‘Byron Georgiadis, a very accomplished criminal defense lawyer from Kaplan and Stratton invited me to lunch and gave me a lot of guidance,” Wetangula says of the attention the cases started attracting his way as his seniors took notice. “He told me, ‘‘When you cross examine a witness - and I know you do it in your own way - you must punch. You must leave a positive impression on the court, because at the end of the day when facts are borderline, the hunch you create has a bearing on the judge or magistrate, because they too exercise discretion.’’’’

After his clients were sent to the gallows by the court martial, Wetangula, now joined by George Oraro, rushed to the High Court to appeal. Here, they won some and had the men set free, and lost some, resulting in Ochuka, Oteyo, Njereman and Ojode facing the hangman’s noose. There was no room for proceeding to the Court of Appeal.

It was game over for the soldiers.

I ask Wetangula why he took the cases.

‘‘When we were being admitted to the bar before Chief Justice C.B. Madan - and this is advise we were also given by Pheroze Nowrojee when he was teaching us at the School of Law,’’ Wetangula says, ‘‘he said once you are in the calling as a lawyer and become an advocate, you always act without fear or favour because you don’t represent what your client did. You represent the rights of your client. If they are coup plotters, you are not part of the coup.’’

As fate would have it, almost immediately, Wetangula became first-name-basis friends and acquaintances with the likes of Fred Ojiambo, Amos Wako, Lee Muthoga, Richard Otieno Kwach, Joe Okwach (deceased), E.T. Gaturu, among other notables within the profession.

‘‘Senior lawyers with half-moon glasses were in their 50s,’’ Wetangula says with a tinge of pride as he speaks of some of his newly acquired friends after he was done defending the coup plotters. ‘‘They walked into courtrooms with their hands draped at the back of their coats, with somebody carrying their books, another person carrying their wigs, someone else carrying their gowns. But here I was, a young man gliding past them going to court.’’

At barely 30, Moses Masika Wetangula had arrived, legally speaking.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

TOTAL PAGEVIEWS

YOU CAN ALSO SEE MORE IN OUR POSTS

Generational shifts

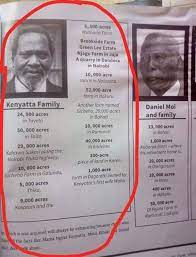

Uhuru secret team to fix succession by 2022

Is the mission Impossible Implementing the Ndung’u Report in kenya?

Uhuru clueless about PS reshuffle list?

How Idi Amin took Uganda to the brink of war in 1976 after attempts to annex parts of Kenya Territory

Komodo Dragon

Victor Wanyama Foundation scholarship beneficiaries undergo mentorship

Time has come that I must speak the truth

Rachael Ruto commercializes her hobby so as to help women

SOCIAL AND EQUALITY TO ALL

My main agenda is adopting a Gramscian theoretical framework, the five parts of this volume focus on the various ways in which the political is discursively and materially realized in its dialogic co-constructions within the media, the economy, culture and identity, affect, and education. We focus at examining the power instantiations of sociolinguistic and semiotic practices in society from a variety of critical perspectives, this blog focus at how applied political linguists globally is responding to, and challenge, current discourses of issues such as militarism, nationalism, Islamophobia, sexism, racism and the free market, and suggests future directions. No peace, no unity, no coexistence hence all becomes vanity...! It's why the world is oval.

Comments