LATEST HOT NEWS IN THE ROOM

Aliveness: Growth will often feel slow in the present moment (if it feels like growth at all...), but the fact that you have been breathing in this space is a sign of aliveness (even if it's small). Assemblage: Be patient with yourself as you assemble the parts of a new dream. It takes time to bring the parts together to create something beautiful. Attention: Let this be a space where you pay attention to the little things that sing to you: "After everything you have been through, it is not too late for you to breathe deep with courage and create something new." Attentiveness: Pay attention. Engage with life. As you observe the patterns and changes, don't forget to notice the good patterns, too. The small movements in the water, building into something larger than what you ever could have imagined. Authenticity: May there be room for you to be present to life in a way that allows you to breathe more freely...beyond the confines of who you thought you had to be. Awar...

HOW THE ANCIENT BUKUSU FORGED THE ART OF WAR

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

....Late into the night, the warriors would chant songs and dance with craze. They would smoke bhang rolls, naturally dried by the sun and rolled on thighs of exotic tribeswomen. Early before dawn, before the first light, they’d arise... by their swords, the enemy shall fall...

Forged on the plains and valleys of Esengeli were rare skills of blacksmithery. From Bamwaya, Bang’ale, Bamuyonga, Baafu, Bakolati and Baleyi clans, emerged steadfast elite ironmongers with extreme talent in forging weapons, cultivation tools and wearables from iron, copper and brass among other metals. Esengeli (land of iron slag) was where the community revived the iron trade after Ethiopians drove them out of Lake of Nabibia region (L.Turkana).

Some of the wearables, still held by community veterans today, included echucheli (copper earing), bichenje (ankle bells), sikhabala (non-iron waist strap), kumukasa (copper bracelet), kumunyuli (anvils), and birere (brass armlet) among others. Apart from producing souvenirs for trade, they also produced an assortment of arsenal meant to reinforce the community’s defenses. Weapons made by community’s elite smiths included embalu (sword), wamachari (short spears), engabo (shield), Lisaakha or lifumo (long spear) and arrows and bows.

Indeed, with such immense talent, the Babukusu were a strong military force feared beyond hills and valleys. Besides, the community was always in command of accomplished military commanders who triumphantly steered them at war time. The few available history rememberers give notable figures such as Mukisu Lufwalula (Omuyemba), Mukite wa Nameme (Omumutilu), Wangamati wa Wabwile (Omukipemuli), Maelo wa Khaindi (Omulunda), Wakoli khwa Mukisu (Omuyemba), Kikiyi wa Weswa ( Omubuulo), Lumbasi we Kangabasi (Omutecho) and Wele wa Kasawa (Omukimweyi) among others.

And yet they were not alone. Side by side, the community was endowed with a rare crop of diviners, future tellers and medicine men and women that gave the critical advice on war. They gave a final word such as postponing wars or giving the greenlight for the mission. Since they could foretell events, their blessings were crucial to the success of the battle. Dominant names here include such as Mutonyi wa Nabukelembe (Omuyitu), Maina wa Nalukale (Omukitang’a), Sing’uru (Omumuki), Wachiye wa Naumbwa (Omukwangwa), Khakula (Omumeme) and lately Elijah wa Nameme and Joash wa Lumoli.

WHY DID BABAAYI ENGAGE IN WARS?

Throughout their migration patterns, Babukusu would encounter many communities who would end up being allies or rivals. Struggle for resources was the central reason why wars happened in the day. Traditionally, Omubukusu was omwayi and omulimi (crop-grower and animal keeper). It’s why in some biilayo (oaths), some clans refer to themselves as ‘Efwe babaayi be Silikwa’ or ‘Babaayi be Embayi’ (We descend from our ancestor who kept lots of cattle at Silikwa/Embayi). Additionally Omubukusu would grow traditional vegetables such as esaka and enderema among others while keeping cattle, sheep, goats and chicken.

To their disadvantage, other Barwa (Kalenjin) communities such as Baruku, Bayobo, Balaku, and even Bamia (Iteso) were traditionally nomadic preying on Bukusu cattle, pastures and crops. Often times, conflicts occurred over lands when incoming communities would seek forceful occupation of existing lands. Such behavior would prompt Babukusu elders to resort to a military action.

Likewise, Babukusu could also wedge war against fellow sub-nations in the Luhyia umbrella. Notable wars include the Battle of Port Victoria (with Banyala) when Mukite wa Nameme beat the war drum in 1822. Again, Babukusu would fight with Banyifwa of Enyanja ya Walule such as the Battle of Rondo where Bukusu suffered a great defeat. In Old Bukusu, Banyifwa or Balatang’eni denotes Luo Nyanza known as Bajaulo in modern dialects. However, the most frequent fights involved Babaayi (Babukusu) and Barwa Barandukhe (Kalenjin and Maasai) who adopted similar migration patterns from Esibakala (Southern reaches of modern day Misri/Egypt).

PREPARATION FOR WAR

It is important to outline that definite clans, known as war clans, had the leading role of military organizations. The clan elders had the role of recruiting new warriors mainly conducted in the forest through various ways such as hunting of blood-hungry leopards in the dark forests. The older warriors taught new warriors fighting skills such as hand combat and use of spears swords and poisoned arrows.

They could also be taught in formation making and varied attacking patterns based on the geopolitical knowledge of the enemy camps. For instance, following the battle of Wachonge, they would learn to fight behind the sun’s rays getting an upper hand over the enemies. It is to be remembered that ancient way of life involved living in large forts housing various clans and families. The new entrants would also be trained to carry out covert spying missions and quick response maneuvers such as abrupt enemy attacks in the forts.

On the D-day, the warriors could sharpen their tools thoroughly like the way Mango did while preparing to face the monstrous dragon. That night, they would smear themselves with oil from Kumutoba (red ochre) for camouflage. They would put on short cloaks (lulware) and don their ankle bells (bichenje).

They would sing all night while smoking bhang rolls to build up psyche. If they kept vigil secretly, they would carry dry stems of Kumufwora tree and sticks from Kumwarakumba through which they would make fire through friction. Early before day-break, they would make way towards the enemy homestead, under the command of their leader.

Very peculiar of the Bukusu warriors, they believed in the gentleman’s war. As they approached the homestead, they would shout, “Elale” (Barwa’s word for ‘Are you ready?’). After the enemy announced that they are ready, they would storm in and dish their share of fury to the host. If the host declined that they were not ready, they would give ample time for them to prepare, even returning back to fight another day. They believed that ungentleman’s war was unethical and dealt undue disadvantage to the enemy. Even, in fighting they would spare and capture women and children. Such a standpoint would change when they faced the Battle of Wachonge (upcoming narration) from which they swore to slay Bamia to the last.

THE MILITARY ORGANIZATION

Mukite wa Nameme was a steadfast military commander who revived official organization of military. The four main distinctions were:

1. Bayoti: These were the scouts and intelligence gatherers. They were proficient in the art of disguise as lost orphans, hunger-stricken immigrants or seekers of potential suitors. They were tasked with analyzing and reporting the status of the enemy forts including number of fighters, how organized and armory locations among others. In some cases, Bukusu girls were ‘intermarried’ in enemy communities with sole purpose of spying before war. Wise military commanders knew that intelligence was critical to war.

Recallable Bayoti included Machote and Wabomba wa Mahaya (Bachemwile), Wabukala wa Malaba (Omuyemba), Walubengo and Silali (Bakimweyi), Watiila (Omukitang’a) and Maelo wa Khaindi (Omulunda).

2. Elamali: These comprised of the vanguard (forerunners) in the attack. They were determined pioneer warriors who would break enemy lines and distort the enemy formation. They would fight tirelessly, ready to give their lives to the service of the community.

3. Eng’ututi: They formed the rear guard. They had two main tasks: offer reinforcement to Elamali as they weakened in the battle and forming a formidable barrier to finish off the enemy. The group also composed of healers who attended to injured warriors and collect bodies of fallen warriors for descent burial if need be.

3. Eng’ututi: They formed the rear guard. They had two main tasks: offer reinforcement to Elamali as they weakened in the battle and forming a formidable barrier to finish off the enemy. The group also composed of healers who attended to injured warriors and collect bodies of fallen warriors for descent burial if need be.4. Special Unit of Baebini: This was a deadly troop of high-skilled warriors also called the interceptors. The name Baebini correlates with babini (night runners). Baebini could come in when the enemy least expected. They were the ‘special forces’ best of the best. They were agile and specialized in distracting or decapitating the enemy within a short time. For instance, they would hide of Kimifutu trees and spear the enemy while passing underneath, would destroy bridges to hinder enemy movement, or shoot lethal arrows from far away in hidden positions.

Notable lieutenants here include Malemo of Bakibayi and his brother Wasilwa, Kasembeli wa Mulaa (Omukwangwachi), Wetayi (Omuleyi) and Siundu wa Bulano (Omumisi).

Next, we'll talk about the Battle of Wachonge. It’s a rare chance into practicalities of war and how the event changed the Bukusu fighting landscape; from a gentleman’s fight to the most lethal fighting ever witnessed.

A story is good, until another one is told...

World street news time brings you the Latest News from Kenya, Africa and the World. Get live news and latest stories from Politics, Business, Technology, Sports and more.

We also mostly keep the cultural practices of the Luhya community,Kenyan communities,Africa and the world at large.Be in touch and get informed. Wele khakaba okaba mala kenya kenya Eyiefwe Ebeo amulinde.Salimia yesu Wa Tongareni.

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

TOTAL PAGEVIEWS

YOU CAN ALSO SEE MORE IN OUR POSTS

Generational shifts

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

A generational shift refers to the gradual transformation of attitudes, behaviours and societal norms as one generation succeeds another, often leading to changes in culture, technology adoption and workplace dynamics. Generational shifts are driven by various factors, including geopolitical events, technological innovations, digital transformation, economic trends and cultural changes. These shifts have a profound impact on the workplace, influencing communication styles, leadership approaches and expectations regarding working conditions, benefits and career development. Commonly recognised generations include Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials (or Generation Y) and Generation Z, each of which has distinct characteristics and experiences that contribute to generational shifts in society. History of generational shifts Generational shifts have been a recurring phenomenon throughout history, shaped by the unique experiences and influences that each generation fa...

Uhuru secret team to fix succession by 2022

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

Uhuru secret team to fix succession by 2022 Eager not to fall into the same trap as that of his mentor Daniel Moi and predecessor Mwai Kibaki where their preferred presidential candidates were beaten hands down, Uhuru Kenyatta has formed a special team to advise him on his succession. The special team comprises Director General of the National Intelligence Service, Phillip Kamweru, president’s kid brother Muhoho Kenyatta, his uncle George Muhoho, Interior principal secretary Karanja Kibicho, former Kenya Defence Forces chief Julius Karangi and former presidential adviser Nancy Gitau. Uhuru’s mother, Mama Ngina, is also joining the team whenever they have a burning issue to discuss. First Lady Margaret Kenyatta and Uhuru political buddy David Murathe, are also in the loop. Unconfirmed reports have it that ODM leader Raila Odinga is also in the team. Those claiming Raila is a key player cite functions influential people surrounding Uhuru have attended in Luo Nyanza. Raila rece...

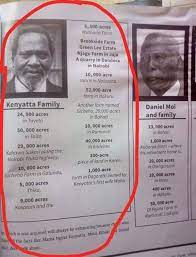

Is the mission Impossible Implementing the Ndung’u Report in kenya?

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

Land continues to command a pivotal position in Kenya’s social, economic, political and legal relations. Perhaps this explains why, when other resources for political patronage have declined at any time in our political history, the ruling elite have resorted to illegally dishing out public utility land. This phenomenon of illegally and irregularly allocating public land to “politically well-connected persons” gains pace just before and after elections. Over the years, a culture of corruption and impunity flourished and went unpunished amongst those entrusted with power over public utility land. 10 Implementing the Ndung’u Report On 30th June 2003, the NARC government appointed a commission of inquiry to investigate the illegal and irregular allocation of public land in Kenya. The Commission came to be known as the Ndung’u Commission, and its report as the Ndung’u report, after Paul Ndung’u, the Nairobi lawyer who chaired the commission. In its report, relea...

Uhuru clueless about PS reshuffle list?

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

Uhuru clueless about PS reshuffle list? Who is doing what and where and to whom in the world of politics • Was President Uhuru Kenyatta kept in the dark on how the list of the Principal Secretaries he reshuffled in September? •The troubles of a lawmaker, who is teetering on the edge after his party threatened to unseat him, are far from over. President Uhuru Kenyatta./FILE Was President Uhuru Kenyatta kept in the dark on compilation of the list of Principal Secretaries he reshuffled in September? Corridors overheard two senior government officials at a famous city club, discussing in low tones how two powerful individuals with huge influence on the President’s decisions were the ones who generated the list of the PSs. The PSs were moved to what were seen to be less lucrative posts. Then the two officials asked the head of state to approve the list before the changes were communicated to the public. At the club, the offi...

How Idi Amin took Uganda to the brink of war in 1976 after attempts to annex parts of Kenya Territory

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WESTERN KENYA CULTURAL HERITAGE

When Uganda’s former leader, Idi Amin, seized power .Jomo kenyatta from the then president, Milton Obote in 1971, his act was received with lots of cheers in Kampala but he would later be seen as a monster after he took up a dictatorial style of leadership. He had come to power with good intentions for his people but as time went on he became power-drunk and started abusing people, historians say.He became ruthless and brutal, repressing the Ugandan people and ignoring their human rights, and subsequently ruined the economy when in 1972, he ordered the deportation of over 80,000 Asians living in Uganda Western leaders, including the United States, cut ties with Amin, and this, coupled with the growing resentment he was getting from his country made him believe that waging war against neighbouring Kenya would save his regime .In 1976, the military dictator attempted to redraw the boundaries of Uganda and Kenya saying that he wanted back all ...

Komodo Dragon

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

The Komodo dragon is a lizard in the family Varanidae, the monitor lizards. It is well known for being the largest living species of lizard. Lizards are reptiles in the order Squamata , which also includes snakes. Lizards are generally smaller than other reptiles, and the Komodo dragon is an example of this. Although it grows to an impressive size, it is still considerably smaller than the largest snakes and crocodiles. A Komodo dragon in a zoo As in other lizards, the Komodo dragon's skin is covered in scales. Most lizards have one or two forms of scales, but Komodo dragons have four. This makes their skin rough compared to that of some other reptiles, and so it is not valued as a source of leather. The Komodo dragon's coloration is generally brown to gray, sometimes interspersed with yellow. The Komodo dragon has an acute sense of smell. Like snakes and many other lizards, it has a forked tongue, which it uses to smell as well as taste. Its main sense organ is...

Victor Wanyama Foundation scholarship beneficiaries undergo mentorship

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WESTERN KENYA CULTURAL HERITAGE

Nine kids who were the first beneficiaries of the Victor Wanyama Foundation scholarship programme are undergoing a mentorship programme in Nairobi.With the schools closed for the mid-season break, the foundation is taking the kids through a three-day mentorship programme, Elvis Majani, the foundation’s advocate, has explained. SCHOLARSHIP “We want to develop the kids into responsible citizens and we are therefore very keen in all aspects of their lives. Some of them are coming to Nairobi for the first time and the excitement they have is evident. Other than just the mentorship programme, we also want them to relax and have a nice time before they go back to school,” Victor Wanyama told Nairobi News. Trizah Shem, one of the beneficiaries, scored 399 marks out of 500 at Nambale ACK Primary School and was admitted to St Bridgits Girls High School in Kiminini under full scholarship courtesy of the foundation. She says her dream of ...

Time has come that I must speak the truth

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

Airtime My friends. My dear Kenyans. I have kept silent for long. Time has come that I must speak the truth. It’s not that I hate them. I deeply Love them They are our Fathers, They are our mothers. They are our Brothers They are our sisters, They are our wives, sons, cousins and daughters. They are our employers They are our employees They are our church leaders They are our mosque leaders They are our political leaders My dear Kenyans What I’m I trying to speak? My speech is about a certain community in Kenya called the kikuyu. It seems this tribe has lost dreams. The communities big dreams are lessening and shrinking. This is a tribe that seems to be in a despair it is in fear of the adventure. The history says, At onetime,the community was chased away from Tanzania It was chased away from Eldoret in 2007''PEV'' It was humiliated everywhere in Kenya in 2007 ''PEV'' The community lives in the national land Everywhere It...

Rachael Ruto commercializes her hobby so as to help women

By PAUL MASIBO WABWAYI NGOME

WORLD STREET NEWSTIME

Rachael Ruto commercializes her hobby so as to help women Mama Rachel Ruto the annual Cross Stitch International Exhibition [Source/twitter/@ssjjkh] Mama Rachel Ruto, the wife to Deputy President William Ruto, has commercialized one of her hobbies to help several women and people living with disabilities. ADVERTISEMENT "I was delighted to officially open the annual Cross Stitch International Exhibition that began at the Safaricom Michael Joseph Center," Rachel tweeted . Through a series of tweets on Saturday, Mama Rachel started that she had officially opened an exhibition where people could buy cross-stitched pieces of art. She invited Kenyans to purchase priceless pieces as they engage with the project that is mainly aimed at empowering women. "Cross stitching is one of my long time hobbies. I was greatly honored to witness a special auction of the priced pieces. Proceeds will go towards supporting women who stitched them while in prison, persons living...

SOCIAL AND EQUALITY TO ALL

My main agenda is adopting a Gramscian theoretical framework, the five parts of this volume focus on the various ways in which the political is discursively and materially realized in its dialogic co-constructions within the media, the economy, culture and identity, affect, and education. We focus at examining the power instantiations of sociolinguistic and semiotic practices in society from a variety of critical perspectives, this blog focus at how applied political linguists globally is responding to, and challenge, current discourses of issues such as militarism, nationalism, Islamophobia, sexism, racism and the free market, and suggests future directions. No peace, no unity, no coexistence hence all becomes vanity...! It's why the world is oval.

Comments